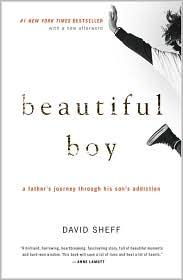

Beautiful Boy

David Sheff

Sheff recounts his experience dealing with his son's Meth addiction. Totally changed how I view addiction. So powerful.

Date Read: 2025-04-23

Recommendation: 5/5

Notes:

Our family’s story is unique, of course, but it is universal, too, in the way that every tale of addiction resonates with every other one.

Why does it help to read others’ stories? It’s not only that misery loves company, because (I learned) misery is too self-absorbed to want much company…This is the way that misery does love company: People are relieved to learn that they are not alone in their suffering, that they are part of something larger, in this case, a societal plague—an epidemic of children, an epidemic of families. For whatever reason, a stranger’s story seemed to give them permission to tell theirs. They felt that I would understand, and I did.

At my worst, I even resented Nic because an addict, at least when high, has a momentary respite from his suffering. There is no similar relief for parents or children or husbands or wives or others who love them.

Our children live or die with or without us. No matter what we do, no matter how we agonize or obsess, we cannot choose for our children whether they live or die. It is a devastating realization, but also liberating. I finally chose life for myself. I chose the perilous but essential path that allows me to accept that Nic will decide for himself how—and whether—he will live his life.

We are among the first generation of self-conscious parents. Before us, people had kids. We parent.

These warnings are meant to increase our vigilance, but it’s impossible to prepare for every possible calamity. It’s one thing to be safe, but panic is useless and too much caution can be stifling.

Drugs shield children from dealing with reality and mastering developmental tasks crucial to their future. The skills they lacked that left them vulnerable to drug abuse in the first place are the very ones that are stunted by drugs. They will have difficulty establishing a clear sense of identity, mastering intellectual skills, and learning self-control.

Internationally, the World Health Organization estimates thirty-five million methamphetamine users compared to fifteen million for cocaine and seven million for heroin.

Al-Anon’s Three Cs: “You didn’t cause it, you can’t control it, you can’t cure it.”

Meth addicts may be unable, not unwilling, to participate in many common treatments, at least in the early stages of withdrawal. Rather than a moral failure or a lack of willpower, dropping out and relapsing may be a result of a damaged brain.

If you subscribe to the idea that addiction is a disease, it is startling to see how many of these children—paranoid, anxious, bruised, tremulous, withered, in some cases psychotic—are seriously ill, slowly dying. We’d never allow such a scene if these kids had any other disease. They would be in a hospital, not on the streets.

Addicts bring up these problems not to clear the air or with the hope of healing old wounds. They bring them up solely to induce guilt, a tool with which they manipulate others in pursuit of their continued addiction.

I tried to instill the idea that morality is right for its own sake. The Dalai Lama, writing in the New York Times, recently explained this in a way that reflects my thinking: “key ethical principles we all share as human beings, such as compassion, tolerance, a sense of caring, consideration of others, and the responsible use of knowledge and power—principles that transcend the barriers between religious believers and non-believers, and followers of this religion or that religion.” To me, those principles are a higher power, one accessible to each of us.

I have learned that the AA adage is true: you’re as sick as your secrets.

Serenity Prayer: “God grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change, courage to change the things I can, and the wisdom to know the difference."

It may be true that suffering builds character, but it also damages people.

Addiction is an equal-opportunity affliction—affecting people without regard to their economic circumstance, their education, their race, their geography, their IQ, or any other factor. Probably a confluence of factors—a potent but unknowable combination of nature and nurture—may or may not lead to addiction.

There’s a practical reason for people to understand that addiction is a disease—insurance companies cover diseases and pay for treatment.

Parents can only be as happy as their unhappiest child, according to an old saw. I’m afraid it’s true.

The disparity between our two worlds continues to stun and overwhelm. Sometimes it seems as if it is impossible that both worlds coexist.

Giving cash to a using addict is like handing a loaded gun to someone on the verge of suicide.

I have learned to live with tormenting contradictions, such as the knowledge that an addict may not be responsible for his condition and yet he is the only one responsible. I also have accepted that I have a problem for which there is no cure and there may be no resolution. I know that I must draw a line in the sand—what I will take, what I will do, what I can’t take, what I can no longer do—and yet I must also be flexible enough to erase it and draw a new line.

These experts agree that, whether in an inpatient or an outpatient setting, it makes little sense to start behavioral and cognitive therapies during the initial withdrawal period. Palliatives such as massage, acupuncture, and exercise programs, along with carefully monitored sedatives, may do as much as anything to help patients make it through the worst stages of withdrawal. Addicts in outpatient programs seem to benefit when they get help making a schedule they can follow until their next session. Drug testing, with severe penalties for relapse, is, the experts claim, essential. Behavioral and cognitive therapies should be added slowly. When they are, they should be monitored so that they reflect an addict’s ability to participate in them.

Addicts are trained to interrupt their normal reactions to anger, disappointment, and other emotions. They are taught about components of addiction such as priming and cueing, which often lead to relapse. Priming (as in priming a pump) is a mechanism that launches a single or incidental drug use into a full-blown relapse. Since addicts may slip at certain stages of their recovery, the program trains them to reframe the incident. Rather than responding to priming, an addict can stop the process at a “choice point.” The moment can be viewed as an opportunity to try an alternate activity. Cueing leads to drug use when an addict encounters a trigger that starts a cycle of intense craving that often results in using.

The idea is that any behavior, including behaviors that seem automatic or compulsive, can become conscious and can then be interrupted. A user can be taught to stop the moving train and call an AA sponsor or drug counselor, attend a recovery meeting, work out in a gym, or other constructive choices. Once again, time in treatment—time measured in many months if not years—is usually required for dramatic change. In the process, the user’s brain is probably regenerating, and dopamine levels may be normalizing. A cycle of abstinence replaces a cycle of addiction.

From “Letter from an Addict” in the pamphlet: “Don’t accept my promises. I’ll promise anything to get off the hook. But the nature of my illness prevents me from keeping my promises, even though I mean them at the time . . . Don’t believe everything I tell you; it may be a lie. Denial of reality is a symptom of my illness. Moreover, I’m likely to lose respect for those I can fool too easily. Don’t let me take advantage of you or exploit you in any way. Love cannot exist for long without the dimension of justice.”

Nic has discovered the bitterest irony of early sobriety. Your reward for your hard work in recovery is that you come headlong into the pain that you were trying to get away from with drugs.

How difficult it is to open up to the world, but how much there is to gain when you do.

Some people may opt out. Their child turns out to be whatever it is that they find impossible to face—for some, the wrong religion; for some, the wrong sexuality; for some, a drug addict. They close the door. Click. Like in mafia movies: “I have no son. He is dead to me.” I have a son and he will never be dead to me.

It is still so easy to forget that addiction is not curable. It is a lifelong disease that can go into remission, that is manageable if the one who is stricken does the hard, hard work, but it is incurable.

I want to escape for tonight, and I want to hide in someone else’s story.

I think, How innocent we are of our mistakes and how responsible we are for them.

Resentment is like taking poison and waiting for the other person to die.

Parents of addicts learn to temper our hope even as we never completely lose hope. However, we are terrified of optimism, fearful that it will be punished. It is safer to shut down. But I am open again, and as a consequence I feel the pain and joy of the past and worry about and hope for the future. I know what it is I feel. Everything.

As to the question of time for therapy, he asked, “How much time is it worth to end a person’s suffering? How much time do you waste suffering now?”

Rather than co-dependent and enabling, with me trying to control him—even if to save him—our relationship can evolve into one of independence, acceptance, and compassion, with healthy boundaries. The love is a given.

I believe that kids don’t need to (and shouldn’t) know every personal detail of our lives, but I will never lie to my children, and I will answer their questions honestly.