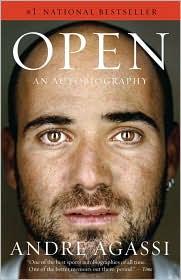

Open

Andre Agassi

Agassi, the world's number 1 ranked men's singles player, hates tennis. Open chronicles his journey toward making peace with the sport and with himself. Couldn't put it down.

Date Read: 2025-09-06

Recommendation: 5/5

Notes:

It’s no accident, I think, that tennis uses the language of life. Advantage, service, fault, break, love, the basic elements of tennis are those of everyday existence, because every match is a life in miniature.

What you feel doesn’t matter in the end; it’s what you do that makes you brave.

A string job can mean the difference in a match, and a match can mean the difference in a career, and a career can mean the difference in countless lives.

Given all that lies beyond my control, I obsess about the few things I can control.

Disorder is distraction, and every distraction on the court is a potential turning point.

This gap, this contradiction between what I want to do and what I actually do, feels like the core of my life.

It’s not the kind of question you can ask my father directly. You can’t ask my father anything directly. So I file it away with all the other things I don’t know about my parents—permanently missing pieces in the jigsaw puzzle that is me.

A friend tells me that the four surfaces in tennis are like the four seasons. Each asks something different of you. Each bestows different gifts and exacts different costs. Each radically alters your outlook, remakes you on a molecular level.

Treat this crisis as practice for the next crisis.

People, I think, don’t understand the pain of losing in a final. You practice and travel and grind to get ready. You win for one week, four matches in a row. (Or, at a slam, two weeks, six matches.) Then you lose that final match and your name isn’t on the trophy, your name isn’t in the record books. You lost only once, but you’re a loser.

To know what your body wants, he says, to understand what it needs and what it doesn’t, you need to be part engineer, part mathematician, part artist, part mystic.

If I must play tennis, the loneliest sport, then I’m sure as hell going to surround myself with as many people as I can off the court. And each person will have his specific role…these people around me aren’t an entourage, they’re a team. I need them for company, for counsel, and for a kind of rolling education.

There are many ways, Gil says, of getting strong, and sometimes talking is the best way.

You can’t win the final of a slam by playing not to lose, or waiting for your opponent to lose.

Qué lindo es soñar despierto, he says. How lovely it is to dream while you are awake. Dream while you’re awake, Andre. Anybody can dream while they’re asleep, but you need to dream all the time, and say your dreams out loud, and believe in them.

There’s a lot of good waiting for you on the other side of tired. Get yourself tired, Andre. That’s where you’re going to know yourself. On the other side of tired.

Faintly I hear my father sniffling and wiping away tears, and I know he’s proud, just incapable of expressing it. I can’t fault the man for not knowing how to say what’s in his heart. It’s the family curse.

I don’t feel that Wimbledon has changed me. I feel, in fact, as if I’ve been let in on a dirty little secret: winning changes nothing. Now that I’ve won a slam, I know something that very few people on earth are permitted to know. A win doesn’t feel as good as a loss feels bad, and the good feeling doesn’t last as long as the bad. Not even close.

Fears are like gateway drugs, I said. You give in to a small one, and soon you’re giving in to bigger ones.

Perfection? There’s about five times a year you wake up perfect, when you can’t lose to anybody, but it’s not those five times a year that make a tennis player. Or a human being, for that matter. It’s the other times.

Simply knowing your enemy is a powerful advantage.

You know everything you need to know about people when you see their faces at the moments of your greatest triumph.

I tell myself: Remember this. Hold on to this. This is the only perfection there is, the perfection of helping others. This is the only thing we can do that has any lasting value or meaning. This is why we’re here. To make each other feel safe.

Rock bottom can be very cozy, because at least you’re at rest. You know you’re not going anywhere for a while.

Pete seems to have the proportions about right. Tennis is his job, and he does it with brio and dedication, while all my talk of maintaining a life outside tennis seems like just that—talk. Just a pretty way of rationalizing all my distractions. I wish I could emulate his spectacular lack of inspiration, and his peculiar lack of need for inspiration.

Our best intentions are often thwarted by external forces—forces that we ourselves set in motion long ago. Decisions, especially bad ones, create their own kind of momentum, and momentum can be a bitch to stop, as every athlete knows. Even when we vow to change, even when we sorrow and atone for our mistakes, the momentum of our past keeps carrying us down the wrong road. Momentum rules the world.

This is why we’re here. To fight through the pain and, when possible, to relieve the pain of others. So simple. So hard to see.

It’s in hospital hallways that we know what life is about.

No matter where you are in life, there is always more journey ahead. And I think of one of Mandela’s favorite quotes, from the poem Invictus, which sustained him during those moments when he thought his journey had been cut short: I am the master of my fate: I am the captain of my soul.

Mandela stands and gives a stirring talk. His theme: we must all care for one another—this is our task in life. But also we must care for ourselves, which means we must be careful in our decisions, careful in our relationships, careful in our statements. We must manage our lives carefully, in order to avoid becoming victims. I feel as if he’s speaking directly to me, as if he’s aware that I’ve been careless with my talent and my health.

I’ve been cheered by thousands, booed by thousands, but nothing feels as bad as the booing inside your own head during those ten minutes before you fall asleep.

It’s so typical in sports. You hang by a thread above a bottomless pit. You stare death in the face. Then your opponent, or life, spares you, and you feel so blessed that you play with abandon.

He goes to his bookshelf, takes down a book. He reads softly:

Though much is taken, much abides; and though

We are not now that strength which in old days

Moved earth and heaven, that which we are, we are;

One equal temper of heroic hearts,

Made weak by time and fate, but strong in will

To strive, to seek, to find, and not to yield

Someone says later that I sounded as if I’d had a near-death experience. More like a near-life experience. It’s how a person talks when he almost didn’t live.

I play and keep playing because I choose to play. Even if it’s not your ideal life, you can always choose it. No matter what your life is, choosing it changes everything.

On the eve of my final tournament, I enjoy that sense we all seek, that knowledge we get only a few times in life, that the themes of our life are connected, the seeds of our ending were there in the beginning, and vice versa.

Do I contradict myself? Very well, then, I contradict myself.