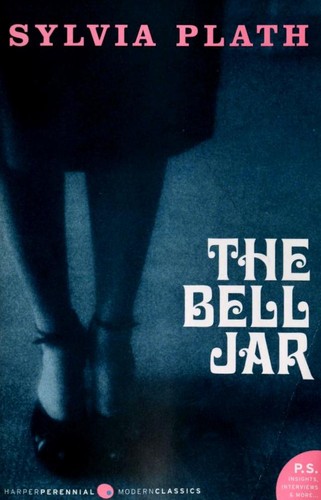

The Bell Jar

Sylvia Plath

Esther Greenwood experiences a mental breakdown. Haunting but at times humorous. Thought provoking commentary on society's attitudes towards mental illness and women's aspirations.

Date Read: 2024-10-11

Recommendation: 5/5

Notes:

A girl lives in some out-of-the-way town for nineteen years, so poor she can’t afford a magazine, and then she gets a scholarship to college and wins a prize here and a prize there and ends up steering New York like her own private car.

It was my first big chance, but here I was, sitting back and letting it run through my fingers like so much water.

There is something demoralizing about watching two people get more and more crazy about each other, especially when you are the only extra person in the room. It’s like watching Paris from an express caboose heading in the opposite direction – every second the city gets smaller and smaller, only you feel it’s really you getting smaller and smaller and lonelier and lonelier, rushing away from all those lights and that excitement at about a million miles an hour.

The silence depressed me. It wasn’t the silence of silence. It was my own silence.

I knew perfectly well the cars were making a noise, and the people in them and behind the lit windows of the buildings were making a noise, and the river was making a noise, but I couldn’t hear a thing. The city hung in my window, flat as a poster, glittering and blinking, but it might just as well not have been there at all, for all the good it did me.

There must be quite a few things a hot bath won’t cure, but I don’t know many of them. Whenever I’m sad I’m going to die, or so nervous I can’t sleep, or in love with somebody I won’t be seeing for a week, I slump down just so far and then I say: ‘I’ll go take a hot bath.’

I’d discovered, after a lot of extreme apprehension about what spoons to use, that if you do something incorrect at table with a certain arrogance, as if you knew perfectly well you were doing it properly, you can get away with it and nobody will think you are bad- mannered or poorly brought up. They will think you are original and very witty.

I wondered why I couldn’t go the whole way doing what I should any more. This made me sad and tired. Then I wondered why I couldn’t go the whole way doing what I shouldn’t, the way Doreen did, and this made me even sadder and more tired.

There is nothing like puking with somebody to make you into old friends.

The floor seemed wonderfully solid. It was comforting to know I had fallen and could fall no farther.

I felt purged and holy and ready for a new life.

‘This Constantin won’t mind if I’m too tall and don’t know enough languages and haven’t been to Europe, he’ll see through all that stuff to what I really am.’

The trouble was, I had been inadequate all along, I simply hadn’t thought about it.

I saw my life branching out before me like the green fig-tree in the story. From the tip of every branch, like a fat purple fig, a wonderful future beckoned and winked. One fig was a husband and a happy home and children, and another fig was a famous poet and another fig was a brilliant professor, and another fig was Ee Gee, the amazing editor, and another fig was Europe and Africa and South America, and another fig was Constantin and Socrates and Attila and a pack of other lovers with queer names and off-beat professions, and another fig was an Olympic lady crew champion, and beyond and above these figs were many more figs I couldn’t quite make out.

I saw myself sitting in the crotch of this fig-tree, starving to death, just because I couldn’t make up my mind which of the figs I would choose. I wanted each and every one of them, but choosing one meant losing all the rest, and, as I sat there, unable to decide, the figs began to wrinkle and go black, and, one by one, they plopped to the ground at my feet.

I needed experience. How could I write about life when I’d never had a love affair or a baby or seen anybody die?

I saw the years of my life spaced along a road in the form of telephone poles, threaded together by wires. I counted one, two, three … nineteen telephone poles, and then the wires dangled into space, and try as I would, I couldn’t see a single pole beyond the nineteenth.

wherever I sat – on the deck of a ship or at a street café in Paris or Bangkok – I would be sitting under the same glass bell jar, stewing in my own sour air.

What was there about us, in Belsize, so different from the girls playing bridge and gossiping and studying in the college to which I would return? Those girls, too, sat under bell jars of a sort.